By February 1944, the United States had been at war with Japan for over two years and had won major naval victories at Coral Sea and at Midway, and ground campaigns in the Solomons and at Buna in New Guinea. But overall victory was a long way off. Neutralization of the major Japanese stronghold at Rabaul on northeast New Britain Island was key to victory in the Pacific. With enemy forces in Rabaul in check the Allies could launch important offensives along the northern tier of New Guinea. The final step in General Douglas MacArthur’s isolation of Rabaul was the capture of the Admiralty Islands. Control of the two major islands, particularly Momote airstrip and Hyane Harbor on Los Negros Island, and Seeadler Harbor at Manus Island, 200 miles north and east of New Guinea and 260 miles west of New Britain, would effectively “cork the bottle” on the Japanese in the New Guinea area and open the way for his return to the Philippines.

Codenamed the “Brewer Operation,” the offensive was planned for 1 April 1944. MacArthur assigned Krueger the job with orders to “establish airfields and light naval facilities” in the Seeadler Harbor area and to seize control of Kavieng, a major port on the northern tip of New Ireland Island to the east. Although 5th Air Force observers reported no resistance on Manus and Los Negros islands, which led them to believe that the Japanese had left the Admiralties altogether, Krueger wanted to be sure. He discounted the reports and did not want to commit troops to an objective in which he was unsure of enemy strength or even if they were there at all. Krueger’s intelligence section estimated that 4500 enemy troops were still on the islands. MacArthur then ordered a reconnaissance-in-force be conducted by 29 February on Los Negros to verify enemy strength and presence. Four teams of Alamo Scouts had graduated from the ASTC on 4 February and were available. This was exactly the type of mission they had trained for, and Krueger realized not only the strategic importance of a successful first mission, but also the need to validate the concept of the Alamo Scouts to ensure its continuation as an intelligence gathering asset at his disposal; one that did not have be shared or placed under the operational control of MacArthur or Australian Sir General Thomas Blamey, commander of all Allied ground forces. Their time had come.

Col. Horton V. White (G-2, 6th Army) [Intelligence Summary – 1945] – “The Alamo Scouts was a valuable military organization designed to give Army headquarters what every Division and lower command already had—an organic reconnaissance agency. It was formed with a view to obtaining strategic and tactical information, primarily for the Army G-2, but concurrently for units being employed or about to be employed.”

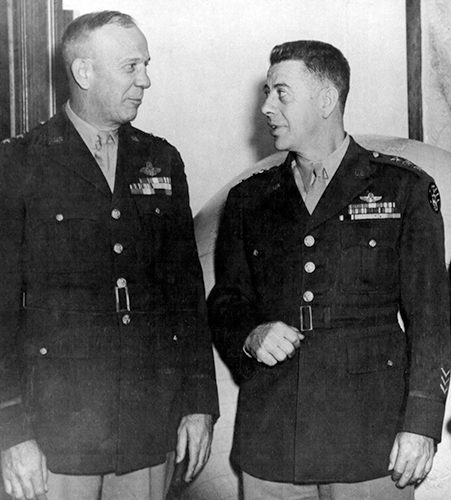

Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger (CG, 6th Army) – “In planning the Brewer Operation, it had been my intention to have an Alamo scout team taken to western Manus Island and have it reconnoiter eastward. But this had to be abandoned when the GHQ instructions for the reconnaissance in force in effect advanced D-day for Brewer from 1 April to 29 February. But it was so essential for us to get more definite information of the enemy than we had that, although the new D-day was close, an Alamo Scout team under Lieutenant John R. McGowan was dispatched at night on 27 February by Catalina plane to the southeast coast of Los Negros for the purpose.” Excerpted from Krueger’s ‘From Down Under to Nippon .’

Gen. George C. Kenney (CG, 5th Air Force) – “On the evening of the 23rd [Feb 1944] the daily reconnaissance report indicated that the Jap might be withdrawing his troops from Los Negros back to Manus. There was nothing for him to stay for. The airdrome installations had been taken out, the last airplane destroyed, and his fuel supplies burned. Even his antiaircraft guns had been knocked out. The message of the evening of the 24th confirmed my estimate…In short, Los Negros was ripe for the picking. I went upstairs to General MacArthur’s office and proposed that we seize the place immediately…On arrival off the island, if the Nips did too much shooting, we could always call it an armed reconnaissance and back out. On the other hand, if we got ashore and could stick, we could forget all about Kavieng and maybe even Hansa Bay. Manus was the key spot controlling the whole Bismarck Sea. That coral strip on Los Negros, a little over 200 miles from Kavieng, was the most important piece of real estate in the theater. The whole Jap force in New Britain and New Ireland could be cut off and left to die on the vine…” Excerpted from Kenney’s ‘General Kenney Reports.’

GHQ, SWPA, Situation Report No. 54/44, (23 Feb 44) – “Aircraft flew low but nil A/A fire encountered. Nil signs of enemy activity. The island [Lorengau] appears deserted…”

GHQ, SWPA, Situation Report No. 55/44, (24 Feb 44) – “No signs of enemy activity on Manus and Los Negros Islands. All crews claim these islands have been evacuated. Grass growing thickly on Momote and Lorengau strips. Runways unserviceable, and badly pitted. No A/A fire, even at low altitude. (The B-25’s flew over Momote strip at 20 feet).”

GHQ, SWPA, Situation Report No. 56/44, (24 Feb 44) – “Both Lorengau and Momote strips are unserviceable. The wrecked aircraft and trucks on Momote are untouched and bomb craters still unfilled. Villages on Los Negros Island appeared deserted and roads have not been used lately. Damage in Lorengau town has not been repaired. No activity of any kind observed.”

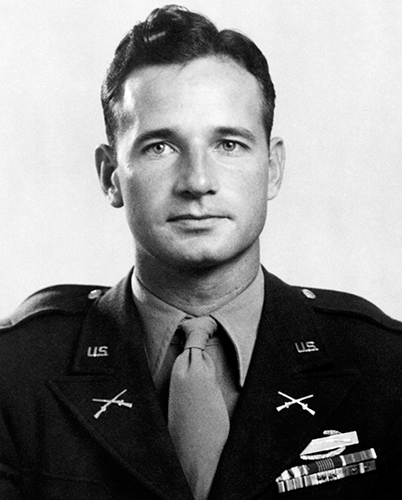

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “The Scouts were on Fergusson Island off the northeast coast of New Guinea and Bradshaw came to me, ‘Mack, I think there’s a mission coming up. Do you want it?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ I was excited and anxious. ‘General Krueger radioed from headquarters, he wants a Scout team. You will leave tomorrow afternoon. Are you satisfied with all your men?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Get all your equipment set to go.’”

I went out to tell the team. They were all in a tent. ‘We got a job coming up.’ One of my men was sick and was replaced by Red Roberts. I selected him from Mike Sombar’s team. I asked Sombar which man he wanted to spare and we agreed on either [Ora] Davis or Roberts. Davis said he’d stick with his own team. Red said, ‘Yes, I’ll go.’

Caesar Ramirez was my assistant; tall, good looking, slim, and conscientious. I assigned men to separate jobs of preparation, equipment, and rations. Had to get ready a ten-man rubber boat, which went on every mission, but was only used once. It weighed 350 pounds and I was so tired of handling it I could have died. We took personal equipment, J and K rations, and anything we were short of we got from other teams. We had an Australian oil compass for each man and we got ready that afternoon. We had a sending off party that night with everybody wishing us good luck. The next morning we went out in a barge and everybody came down to the LCM wharf to see us off; envious and glad they were not going. We went from Fergusson to Goodenough Island where the landing strip was to catch a plane, and we arrived about noon, but the plane didn’t arrive until 4:30. The pilot said he couldn’t take us and that he’d be back in the morning to take us. He was going to Milne Bay to spend the night. I argued with him that the job was for 6th Army, but he didn’t care! I told Colonel Bradshaw what happened and he was mad, ‘I’ll go up and see whether the pilot or General Krueger is running 6th Army!’ The next morning we went back again, the colonel with us. Barnes went too. The plane landed and Colonel Bradshaw talked to the pilot immediately. The captain that had talked so big to me was standing at attention and only said, ‘Yes, sir! Yes, sir!’ The colonel said, ‘When General Krueger asks for planes to take men to headquarters, they usually go!’ The captain said, ‘I didn’t know it was as important as that.’ Bradshaw replied, ‘EVERYTHING in the Army is important!’

So, we took off to Finschaven and arrived about an hour later. Barnes had been to headquarters, but I hadn’t. He knew Colonel Rawolle, but never took the trouble to introduce me to him, and he proceeded as though he were going on the mission. I couldn’t contradict him because all I had was verbal orders from Colonel Bradshaw. Rawolle told us both what the mission would be. I still didn’t know much of what was going on. Evidently, Colonel Rawolle didn’t know either from the way Barnes was talking. We had to get our aerial photographs and maps and study them. Colonel Rawolle finally asked, ‘Which one of you is going on this mission?’ Barnes said, ‘I want to go.’ I said, ‘I don’t know. Colonel Bradshaw told me I was going.’ Rawolle said, ‘All right, Mack, you are in charge of this mission. Barnes can do anything he can to help you get ready.

I turned all the work over to my second in command to study maps, etc., while I made an aerial reconnaissance. Colonel Rawolle called up 5th Air Force and arranged for a B-25 to take me and the Navy pilot, Lt. (jg) Pierce, and Barnes. We got in the B-25 and the Navy pilot and I were in the nose where we could see better. I forgot to relieve myself before starting. Took two hours to reach the Admiralties where the mission was to be. The pilot made a power dive from about 3000 feet to pass as quickly and as low as possible over Momote Airstrip, which was Jap held. It was just a blur to me. I was more conscious of the fact that I’d just relieved myself! Either the pull of gravity or being scared. Must have been gravity, for no ack ack from the field. It embarrassed me. When I looked up at the Naval lieutenant, the silly grin on his face caused me not to bet the same thing hadn’t happened to him. Before we circled to make a run over the coast we saw a barge, which was strange, for 5th Air Force said the Japs had evacuated the place. We made the run over the coast where we were supposed to land and so that Pierce could be sure of open water. Then we flew back to Finschaven and got back two hours later.”

Lt. William F. Barnes (Team Leader) – “Once we completed our training a mission came up in the Admiralty Islands. Two of us were chosen, my team and John McGowen’s team. Colonel Bradshaw flipped a coin to see who would get the mission and McGowen won. We worked together in teams. We were the contact team. We flew in by PBY and put his team into the Admiralties. They went in in a rubber boat and we picked them up 24 hours later. The night before the mission General Krueger briefed us in his tent and spoke to each one of us. He was trying to build up our confidence.”

Lt. (jg) Walter O. Pierce, USN (PBY Pilot) – “Two days before the mission Lt. McGowen and I were in the nose of a B-25 and flew over Manus Island to check to see if there were any objections to landing in the spot that we had picked, and there were small Jap boats all over the place. The flight was to give McGowen a chance to look at the island.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – I had to go up to 5th Air Force Headquarters. Met General Whitehead. He was bending over a map of Los Negros telling Colonel Rawolle that his attached B-25s were going to make runs parallel to the airstrip with a slight sector of strafing at the northwest end of it. I didn’t know what he was talking about when he asked, ‘How does that suit you, lieutenant?’ I said, ‘It won’t bother me any.’ He said, ‘Damnit! I know it won’t bother you! Will it help any?’ That was my first knowledge that all those planes were to HELP us out. Also learned that they planned a big attack at daylight, as well as the one he was explaining that would be at 10 a.m.

I went back to talk to Colonel Rawolle. He said, ‘I think the mission will be all right, because the plane will land you before daylight and you’ll be ashore before daylight.’ But he didn’t know that a PBY pilot has to be able to SEE the water before he can land on it. While I was there the chief of staff, General Patrick, said that General Krueger wished to see us about 10 p.m. So, we went over to the general’s house and were introduced personally, each man to him, by General Patrick. Krueger told us how important the mission was and that what we did or did not do would involve the lives of many American soldiers. He said he was doubtful about the information the 5th Air Force had given about the Jap’s evacuation of the place, and that it was up to us to find out if the Japs still held the strip. Then he asked General Patrick what kind of communication 6th Army would have with us while on the mission. General Patrick said, ‘We’ll find out when they get out.’ General Krueger said, ‘That’s not satisfactory. We want to know when they find out.’ General Patrick said he would arrange it. That was my first intimation that Krueger doubted our getting out, for I had thought it would be a snap. General Krueger said, ‘You are a good bunch of boys and this is the first Scout mission. The future of the Scouts may depend on what you do.’ That put a lot of weight on me, for I saw what Colonel Bradshaw was thinking, but wondered why he picked me for the job.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “Before we left General Krueger’s house, he looked us all over and spotted a little white tag on Gomez’s camouflage suit and remarked, ‘That white tag more than offsets the value of a camouflage suit.’ Which was right. Then I didn’t know whether I was cussing myself or Gomez more for the error, or for my not checking. Made me feel pretty small to know it took a general to spot so small a thing when so much depended upon everything. General Krueger asked me if I or my men knew of any future operations. I said no, and he stressed the fact that if we didn’t get out, to be sure to stay away from Momote Airstrip. We left. We had to figure out a system of communication. We decided that the only possible means was for us to take a 536 Walkie Talkie and contact a B-25 that would fly over at 4 p.m. I wasn’t sure it would work. Never had tried it, but field manuals said it would work. I didn’t want to be too worried with a radio anyway. We left and went out to the PBY tender Half Moon about midnight to wait until 3:30 a.m., when a PBY would take us to Los Negros. I was dead tired, but hadn’t had time to study the maps in order to approve the procedure that Ramirez had outlined for us. He’d written a report on what he thought we would do throughout the mission and turned a copy in to Colonel Rawolle. I studied the copy he’d kept for me. When 3:30 came I was really cussing that airplane pilot for not bringing us up sooner, and wished I could knock his head in for putting his dinner engagement in Port Moresby ahead of duty.

We took off in the PBY and headed for Los Negros. We were out about an hour when we ran into awful rainstorms. It was rough. Pierce, the pilot, found a clear spot in the storm and started circling. Another PBY found the same spot and was circling too, which we didn’t know, and we missed him by about 50 feet. We circled for about an hour, and I was certainly relieved when Lt. Pierce told me it was impossible for him to get there at the estimated time of arrival and that he was certain that the light fighter escort which was to meet him there could not make it in that weather. He turned around and went back, and I slept like a baby, the first sleep I’d had in 24 hours.”

Lt. (jg) Walter O. Pierce, USN (PBY Pilot) – “I was supposed to drop the team off, but there was also supposed to be an Air Force bombing mission to distract the Japs attention from our plane. But we had to cancel en route because they didn’t have a bomb attack at all, so the ready plane the next day took my flight. Then I had to go in the following early morning and pick the group up. It was a group of six Alamo Scouts, Lt. McGowen and his five men.”

Patrol Squadron VP-34 (War Diary – 26 Feb 1944) – “Lieut. (jg) Pierce (08487) on special mission. Forced to return due to weather conditions.”

Col. Horace O. Cushman (AGF Observer) [4 Mar 1944] – “26 Feb 0330 – Took off in Catalina, proceeded about two thirds of the way to area, the pilot decided to return because of bad weather conditions and inability to contact fighters and bombers. (Note: weather conditions prevented fighters and bombers from coming to area).”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “We got back to the tender and I radioed Colonel Rawolle what had happened. He said, ‘Stay on tender until I get there.’ I still think that storm was a miracle, for we’d planned to stay on the island for two days, which we never could have done. We slept all that day, and got ready to leave that night as before. Roberts didn’t tell me that he had dysentery and was having to run regularly every hour. Our mission was changed so that we’d get in one day and out the next. About 3:30 I was well rested, but worried because Lt. Pierce got sick and another pilot had to take us in. As we were going, I was hoping we’d hit another rainstorm, but we didn’t. I was trying to pray awful hard, but John Leugoud kept whistling over and over, Lay That Pistol Down, which continued until we landed. We didn’t do much talking, and I’m sure no one did any sleeping if they had the same empty feeling I had. I couldn’t keep from looking at my watch. About 30 minutes before we got there we started getting our gear together and putting camouflage paint on our faces. As we drew near the Los Negros coast we could see the bomb flashes and tracer bullets of the strike that was going on. The pilot didn’t try to land until it was good daylight, which increased my uneasiness. Just as we were landing, Gomez made a big face and pointed at his stomach. I thought that he was trying to back out, and I spoke rather harshly, ‘I don’t give a damn if you are sick. If you don’t want to go, sit down and keep out of our way!’ About that time, part of the PBY crew threw out our rubber boat and pulled the automatic inflation handle. The Navy gave us hot coffee just before we landed. It tasted good. As I was going to the back of the plane to get out, I slipped and got a bad skin on my shin. That didn’t improve my feelings. I was surprised as I sat down in the back of the boat in the coxswain’s position to see that the sun was coming up, which was a long ways from the statement Colonel Rawolle had made about going in before daylight. Gomez was in front of the boat acting as lookout and security and I was in the rear steering. The other four men were rowing. I guess they all were as scared as I was, but none showed it. I thought they were a bunch of damn fools for going in in daylight, and I was still mad at Gomez and kept looking at him and hoping that if we got shot at he’d be the first one to get hit. As we drew closer to shore, I got to wondering if he did get shot, if I’d see him fall before I heard the shot. Just as we reached the shore, a rough coral cliff, he jumped out and pulled the boat up closer. Others jumped out also, but Caesar Ramirez jumped in and went over his head. Since I was last man in the boat, I was careful not to make that mistake. Then I was thankful for the thorough training that Colonel Bradshaw had insisted upon at the center, for we’d got as near perfect training as one could get without the actual experience. Four men rushed out to their security positions while the front flanks and rear deflated the boat and rolled it up, put it in a depression between two tree roots, and covered it over with leaves and brush.”

Pfc. Robert W. Teeples (Barnes Team) – “At the time McGowen’s scout team was chosen to reconnoiter the Admiralty Islands the Commandant asked for volunteers to assist the team to debark and embark. I was pleased to have been selected to assist the team. We loaded onto a PBY flying boat. It was dark when the plane took off and it seemed like we went for miles on the water before we could no longer feel the slap of the waves. We flew into a thunderstorm and it sounded like the old plane was creaking and the wings almost flapping. We had flown for quite a distance and I was sitting in one of the blisters looking into the darkness when something besides the lightning seemed to flash by. I thought it had been my imagination until one of the crewmen that was in the other blister asked, ‘Did you see that?’ I told him I had seen something but couldn’t imagine what it was. He thought it was probably an exhaust flash from a Jap plane. About that time the radar man confirmed that he had picked the plane up on his screen when it was about five miles out and it was headed right for us. After we helped the team disembark, the PBY took right off and went back to base…”

Patrol Squadron VP-34 (War Diary – 27 Feb 1944) – “Lieut. [James F.] Merritt (08139) landed 6 Army Rangers [Alamo Scouts] off the south shore of Los Negros Island at daybreak to carry out scouting operation in preparation for invasion. Lieut. (jg) [Ross B.] Vandever (08496) covered the operation.”

Col. Horace O. Cushman (AGF Observer) [4 Mar 1944] – “27 Feb 0305 – Took off in Catalina. 0645 Catalina landed about 500 yards offshore—rubber boat put out—inflated. This all done in daylight. 27 Feb 0745 – Landed in rubber boat; carried boat ashore, deflated it and hid it in trees. Put out three men as local security—one man to each flank and one inland about 50 feet. The sure at this point was a coral shelf two or 3 feet above the water line, very rough interspersed with numerous 2 to 3 feet deep holes. Scattered stunted pandanus palms cover the area inland to about 50 yards. The local security could see the men working around the boat when they moved. Deflation of the rubber boat required about 15 minutes. They thought the noise of the escaping gas could have been heard. 0800 – Started inland on azimuth of 45° in column of files, the patrol leader leading, others following about 5 yards maintain visual contact. One of the corporals said he could always see the first two men behind him, but seldom the third man. 0945 – Had moved about 1500 yards inland when they noticed marks where a path had been cut through the jungle. A vine was stretched along one side of the path—the leaves in vine still green. They thought it may be a trap of some nature. They now think it was to mark the profile of the trench.”

Lt. Milton Beckworth (Instructor) – “I believe they had 52 bombers and 52 fighter planes covering this PBY landing, strafing the coastline, dropping bombs, and doing everything while these men were landing by PBY and going ashore. The next morning when they were supposed to be picked up by the PBY, the same air cover was supposed to be there, but the only thing that showed up was the PBY. You can just imagine how tense these boys were. It was a difficult mission.”

Pfc. John C. Pitcairn (Barnes Team) [War Diary – 1944] – “Two teams of Alamo Scouts left Saidor in a small landing craft to Goodenough Island, then continued to Finschaven by air, a distance of about three hundred miles. This was a leading American supply base; therefore, we went to headquarters for our tents and supplies. Both patrols were previously briefed for this mission. However, orders came in that the other patrol would go on this mission. The other team of scouts left that night in a seaplane, also some of our boys went along for the ride. However, a storm came up that compelled them to return to base. They were so close to another plane that they almost had a collision. The next night the scouts left on their mission, the seaplane returning to base at 10 o’clock the next morning. The six scouts, yes, six of the most gallant men that Uncle Sam ever had the pleasure of knowing, got into their Navy rubber boat and bravely rowed two hundred yards to the coast of Los Negros, a small island nine miles square and occupied by an estimated five thousand Japs. We could not sleep so well because we knew the danger that lay ahead of those boys. We anxiously awaited the arrival of the plane the next morning at ten o’clock.”

Toyamo (Japanese soldier on Los Negros) [War Diary – 28 Feb 1944] – “An enemy floatplane made a landing and they reconnoitered the coastline. There is a great possibility of enemy landing.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “I took the lead and used a little waterproof matchbox compass for direction and my watch for a speedometer. It’s not easy to go through enemy territory always looking for the enemy, and yet having to concentrate on how far and what direction one is going—and keeping check on men behind you at the same time. About 9 a.m., McDonald made a face that he had to have a bowel action. We stopped, and I thought how foolish the Army was in making a camouflage suit without a rear exit! McDonald could have been easily captured, and his backside was a lot larger than the little white tag that General Krueger had complained of. Just before 10 a.m., we ran into the first signs of human habitation, a bunch of long vines tied together going in a general direction perpendicular with our line of march. I couldn’t figure out what they were for, but thought perhaps it was a booby trap. So I sent the two men behind me out to either side to see where they led to and what they were connected to. They found where it was disconnected. Then I knew it was no booby trap. I found out several months later that the Japs used those vines to feel at night to maintain their direction of march. Just as we passed those first vines we heard a short burst of machine gun fire, which sent cold chills up our backs, for then I suspected the 5th Air Force was wrong, and if they were, what in the hell were we doing in there in broad daylight? But if Japs had seen us, why had they left us alone so long? That machine gun burst must have been the air raid warning, for a moment later we heard a bunch of B-25s coming. Sure enough, at 10 o’clock like the general said, and he was sure right when he said he knew they wouldn’t bother us, for it was sweeter music than any lullaby. We saw only one of the planes since they came in low over the airstrip about a quarter mile away. But that quarter mile didn’t take up much of the jar and the bang of 1000 pounders when they went off. As soon as the bombing and strafing stopped, we started forward again and heard what sounded like a man imitating a bird dog, which was what I thought it was, until the voice broke into hysterical screams. Also, we could hear other voices which sounded like Japs. I still don’t know what the scream was—a wounded Jap or a native being tortured or a man gone screaming mad.”

Col. Yoshio Ezaki (Japanese Commander, Admiralty Islands) [War Diary – Feb 1944] – “The enemy is continually bombing and reconnoitering by air and the enemy shelling is especially severe. Situation desperate.”

Col. Horace O. Cushman (AGF Observer) [4 Mar 1944] – “27 Feb 1030 – About 300 yards farther ran into a trench. It was zig-zagged—about 50 yards long, 2 feet wide by 2 feet deep, with automatic weapons pits dug into the forward edge. The spoil bank was well camouflaged—it was not seen until the patrol leader was within 5 yards of it. No bunkers had been built but scattered trees had been felled some distance behind and even the tree stumps had been camouflaged. At about this time, our bombers came over a long and straight north of the strip. The patrol members stated that their inclination was to stand up and cheer them in. A machine gun was heard firing some 400 to 500 yards to north..”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “We had slowed down considerably, lifting each foot carefully and setting it down noiselessly, when all at once I looked down and saw a trench that was freshly dug in the white coral rock, yet I couldn’t see it more than 10 feet away. The spoil bank was well covered over, impossible to spot from the air. It was a short trench about 60 yards long, but back of it echeloned along both sides were others. We crossed three more and all the time hearing more and closer voices. Finally, I looked through the brush and saw the silhouettes of two men that were talking. I could see them through a window against a light background, yet couldn’t see the house. I decided to rest awhile there, and thought to myself, Well, I’ve seen my first Jap. I was lying there nibbling on a blade of grass, but I didn’t realize how relaxed I had become until the grass slipped out of my mouth, which let me know I had dozed off for a second. That gave me quite a scare. We circled to the right of the house and ran into a trail, well worn, yet narrow and completely shaded by trees. We crossed it and went about 50 yards. I came to an open place which I thought was a good place to see from. I caught a movement over to my left and it took a lot of courage to keep from running. Maybe I was just scared stiff. Sure enough, the movement was a Jap walking down the trail about 10 feet in front of me with nothing between me and the Jap. He walked right by me, never saw me. That was one time that this face dye and camouflage suit saved me and my boys. Just as soon as he had passed, I got low and tried to crawl back from the trail, but more Japs kept coming down the trail. It gave me a great sense of security to see Red Roberts sighting down the barrel of his carbine following the Japs along the trail. I couldn’t see behind me to see when they were coming, but he would nod or shake his head that it was clear or not. Even crawling on my stomach, my back side felt like a red beacon trying to attract the Japs’ attention. When I got back from the trail I went to the left and saw more Japs, then turned back to find the trail, and there were still more Japs. Japs walking on three sides of us with a house on the fourth, none of which was more than 30 yards away. About that time, I was wishing that Lt. Barnes had taken the job, for I’d have given all I ever hoped to own to be away from there. I was just scared to death. Then I got to thinking how nice it would be if this were just another of our problems back at the Training Center, where if I did get caught, I’d just laugh and say, ‘I’ll do better next time.’ And then I thought, Oh well, this time tomorrow we’ll be back at 6th Army and be heroes—if we live that long! All those Japs moving around must have finished eating lunch, for they were not moving around when we went into that spot. I couldn’t think why I hadn’t paid more attention to all the voices I’d heard on the way in, or why we hadn’t run into some of them. Must have been walking away from voices we’d heard. I was beginning to get worried about my being afraid and about my men being afraid, but in a few minutes McDonald came up to whisper, ‘Do you want me and Caesar to go on up to the edge of the airstrip?’ This showed I needn’t worry about my men’s fear. But I didn’t think that any more information could be gotten without a great risk to our losing ourselves and that information we already had. Since 4 o’clock was approaching, we still had to get away from the Japs to talk on the radio to the plane due over us at that time. So I started back over the way we had come, and as I approached the first trail we had crossed, I got a shock when I saw a Jap running down the trail hollering to someone else on the trail, and although I’m the only one who remembers hearing it, I would swear that he yelled along with some other things, ‘Alamo Scouts!’”

Sgt. J.A. “Red” Roberts (McGowen Team) – “I had one of them Japs right in my rifle sights. It was sure hell not being able to cut down on the son-of-a-bitch!”

Col. Horace O. Cushman (AGF Observer) [4 Mar 1944] – “1220 After moving forward about 100 yards, they heard sounds of talking—waited about 30 minutes—talking continued. The patrol moved forward very carefully a few feet and could see the dim outlines of a grass hut through the doors ( or open sides) they could see the outlines of three men. The patrol moved to the left and passed around the other trench. The original plan had been to proceed to the river and separate into three groups of two to observe toward the strip. They crossed a well used footpath running behind trench. The trench also had a buying strung along it. Another trench—evidently a part of the same series was seen to the right. They moved forward again about 50 yards and saw a Jap standing up some 15 yards to their front. He moved to the right and right rear evidently along the trail. He was followed by a more moving from another house ( the outline of which could barely be distinguished) in groups of one or two along the same trail. Could not see their weapons. They were taking things easy walking along the trail. One of them carry something heavy in his left hand—later heard sound of metal against metal—might have been shovels. Platoon leader figured they had been back eating their noon meal.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “As I lay there waiting for a break in the Japs that were walking by, a Jap stopped on the trail right in front of me, looked in my direction and stared toward me. He came to within five feet of me and looked at me and all around me, all the while I was trying to keep the center between his eyes in my peep sight, but I was shaking, so it was hard to do. I was squeezing the trigger of my carbine, waiting for the instant that his eyes focused on me before shooting. I got ticked at myself for being so scared, for there was the poor unsuspecting Jap just about to die and he wasn’t scared at all. However, he didn’t know what I did. Just as I was about to shoot him, he looked up in a little tree beside him, shook it, and walked back to the trail and on. I still don’t know why he walked off the trail, or if he was looking for us, nor how he kept from seeing me. I eased up close to the trail, which was an S shape, and I couldn’t see around either ‘corner’ of the trail to see if more Japs were coming. But when it was clear, I made a dash across the trail, none too quietly but with speed. Three more of my men got across all right, but a Jap showed up and made the other two men wait awhile. I moved on up about 50 yards and waited for them, but when they crossed the trail they went to the left and missed us. After waiting about 30 minutes, I decided they were not coming and that they’d go on anyway to where the boat was. We headed back toward the boat and came to a rock cliff, which we climbed and got to the top of just before 4 o’clock. Sure enough a B-25 came over and circled. I turned on the 536 and was expecting Barnes to be in the plane, but it was Colonel Rawolle. When I heard his voice, ‘Violet to Rosebud’, repeating about five times, that little 536 sounded like a loudspeaker. I don’t see how the Japs in Tokyo kept from hearing it. Yet he had trouble receiving me. He wasn’t very well informed on radio procedure, for every time the plane got farther away and he couldn’t hear me, he’d come back with his ‘Violet to Rosebud’ about five times until I finally told him to shut up. The only message I got to him was, ‘Lousy with Nips’, which was a code between me and Barnes that there was an un-estimated number of Japs all over the place. Others were, ‘No Nips’, which meant I saw no Japs, ‘Some Nips’, about 10 or 20, ‘Many Nips’, a hundred or so. I found out later that my message was almost useless since Colonel Rawolle didn’t ask Barnes what it meant. After Colonel Rawolle asked me about six times to repeat, and I’d spelled out ‘Nips’ as many times, I told him I was getting out since the Japs were bound to have heard me, and I didn’t want to stay in one place too long.”

Col. Horace O. Cushman (AGF Observer) [4 Mar 1944] – “The patrol had closed up into a small diamond. The patrol leader crawled back to talk over the situation with Sgt. He thought of staying there until dark in as much as part of the plan was for him to contact a B-25 by radio that afternoon, he decided to back out of the area and moved back toward the shore. He considered it too dangerous to ‘talk’ to the plane from that location. He could foresee difficulty in recrossing the trail. Just before he reached it, Jack returned along it from the first house, stopped opposite him, took two or three steps toward him, turned around and walked off to the left. The control is quite sure that if their faces had not been ‘painted’ with iodine and green ink they would’ve been discovered. After the Jap passed down the trail the patrol leader looked both ways along the trail, the man on his right and left nodded their heads and he crossed it. The process was repeated until all but two had crossed. Then the remainder of the Japs came back along the trail separating the two groups of the patrol. The patrol leader said he had just about made up his mind to start shooting but all of the Japs when along, looking down at their feet, and the extreme tension was over. He and the three men waited about 15 minutes, tried to find the other two and not succeeding, started back to the beach. On the return trip they got off their bearing a bit and came out on a 50 foot high coral shelf overlooking the lake. It did not show in the mosaic which they had nor could they find it in the vertical photographs of the area even with the aid of a stereoscope. 1600 – They heard and saw the B-25 over them, contacted by radio after considerable difficulty, and finally gave them the message, ‘Could not get to river. Lousy with Japs.’ They discover later that the message was reported to Task Force as: ‘Gotten to river, saw lots of Japs.’

Gen. George C. Kenney (CG, 5th Air Force) – “Both Whitehead and Cooper were worried about the show and my having gotten myself and MacArthur out on a limb. I argued them into a state of partial reassurance but had to start all over again when on the morning of the 28th a report, from some scouts that Krueger had sent to Los Negros the night before, stated, ‘The place is lousy with Japs.’ I told Whitey and Coop that the scouts had seen only one spot on the south end of the island where we could expect the Japs to be, to keep away from the airdrome and camp areas which were bombed. Moreover, if there were as many as twenty-five Japs in those woods at night, the scouts would think that the place really was ‘lousy with Japs.’”

Lt. George S. “Tommy” Thompson (Team Leader) – “I remember the selection of teams from the class and the sweating out of the first mission. Mac’s team was lucky, and justly so, because that team was one of the best to ever come out of the ASTC. The mission on Los Negros was a ‘natural’. However, as it turned out, the boys had to make a daylight landing in the Admiralty Islands, and backed up by the tail end of a ‘cat’ [PBY] streaking for home as fast as its propeller would carry it. The reconnaissance was successful and the team was picked up on schedule. However, between that landing and pick up, the team went through some of the closest contacts that any subsequent team ever made. Twice they were passed by patrols, and each time a few feet distance. Some excellent face camouflage, cool nerves, and a lot of luck kept the fellows from being observed. It takes something besides fear to freeze you in your tracks and not shoot, move or turn, or run like hell when a Jap patrol stops near a man, or when one Jap walks to within five feet of him and then turns around and rejoins the patrol. Did he see me? Should I run? Is he going to alert the rest of the patrol? Should I shoot? Those are some of the questions that rush through a man’s mind at such times. To me that was a wonderful display of cool nerves.”

Col. Horace O. Cushman (AGF Observer) [4 Mar 1944] – “1900 reached the shore near where the boat was hit and saw the other two men coming along the edge of the beach (coral) from the east. In the meantime, these two men after being separated from the patrol leader and remained with him, turned a bit to the left, across the trench and path, and moved off in an azimuth of 225°. They reached the shore At about 1845, were not sure where they were, turn to the west for about 300 yards, saw evidence of the path used by Jap patrols and a fresh Jap trail in a small patch of sand, turned back to the East, passed by the boat, retraced their steps and ran into the patrol leader and his men. They stayed in that area all night in three groups of two each, about 50 yards apart, one man of each group staying awake this time.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “We headed back toward the beach and I came out within 50 yards of where the boat was hidden. I was the only one out of the six that recognized the spot, which taught me a good lesson, that if you hide the boat so good you can’t find it, it might be better to leave it in plain sight and risk the enemy finding it than not to be able to find it yourself. The four of us settled down to wait for Ramirez and McDonald when we heard a big noise, and that was sure enough the two boys walking along trying to make noise so we would see them. They were lost. Then when we did recognize them, the other three boys ran out to meet them and they indulged in a bit of back slapping and hugging—a happy reunion, but somewhat out of place. By that time dark was gathering, so we split up into groups of two about 50 yards apart around the boat to wait for morning with the understanding that one man of each group would be awake at all times. I was with Red and he was to take the 6-to-12 watch. I tried to sleep and was just dozing at dusk when I heard a twig snap right beside my head. I jumped and scared a wood hen about one tenth as bad as she scared me, and it took off in a whirl of wings. I lay back down, weak all over, and thought about dying from heart failure, which might not have been far wrong since I had trouble getting my breath for the rest of the night. Started looking at my watch at 11 p.m., waiting for Red to call me at 12. About 3 a.m., he crawled over to tell me it was my time to keep awake. I told him that it was his time, and that he’d had more sleep than I had. Just about the same thing happened with the other groups. Just before daylight we all got together, got the boat out and started to pump it up, but the pump wouldn’t work. It would suck out instead of pumping air in. About that time, I heard the Catalina coming, but our radio failed to make contact. However, when they passed over, I blinked them by flashlight, which was also in our communication plans.”

Col. Horace O. Cushman (AGF Observer) [4 Mar 1944] – “28 Feb 0530 – One man from each group returned to the boat and started to inflate it. They had difficulty inflating the boat as the pump did not work too well. 0600 – They heard the Catalina over them—gave the prearranged flashlights signal in the Catalina and. It was so dark they could barely see the outline. They signaled again, as they were afraid the crew could not see them Catalina turned and came in to about 300 yards from the shore. The pilot said the flashlight looked as big as a searchlight. Catalina could not stop us engines and was moving back and forth slowly. The first four men guided the flying boat easily, the remaining two had a difficult time nearly be run over and swapped. Finally clambered in the pilot took off not giving them time to sink the rubber boat. The return trip was made without incident, except that the fighters which were supposed to cover them after daylight, never were contacted.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “This time the Catalina landed even before I could see the surface of the water. In the meantime, the boys had got the boat inflated and we started rowing out to the plane. When we got there, the crew threw us a rope out the side blister and four of my men got aboard. Just as I started to go aboard, the pilot gunned his starboard engine to keep his tail and guns toward the shore. When he did that, his extra speed swamped my rubber boat throwing me into the ocean. Red pulled me back into the boat. He circled three times trying to pick us up. We’d made the mistake of handing in our paddles first. The third time he passed by us I noticed that the nose gunner was screaming at me to keep my head down. I didn’t know why until the prop clicked the cap off my head. His fourth time around he hit our boat head on, but luckily the boat lodged at the bow and didn’t go under—it would have drowned us both.

Red and I crawled into the nose turret down between the pilot and co-pilot. I was surprised to see that Lt. Pierce was the pilot. He was very nervous and spoke rather harshly to me. If I’d said what I was thinking about him, it would have been more than harsh, for his gunning his engine almost caused me to drown and delayed the pickup 30 minutes, and besides, his two measly .50 caliber machine guns were not much protection against the large naval guns on shore. However, had he known they were there, chances are he wouldn’t have landed at all. However, he had reason to be afraid for his fighter escort hadn’t arrived. He took off and I was a happy lad. When I heard the plane hit the last wave and stay airborne I let out a big yell. I felt rather self-conscious until I saw the other boys had all done the same thing. I even soon got over my peeve at Lt. Pierce when all the crew came by and apologized and said that was the lousiest pickup they’d ever seen. They gave us hot coffee and fresh apples, and they were all anxious to talk with us. But we had orders not to talk to anyone, not even to compare notes. A pretty good idea as I found out later, for just talking to each other, we could influence each other in what we thought we had seen. I got my first idea of what it felt like to be looked at with awe when we got back to the seaplane tender and all the sailors gathered around to look at us! We must have been a funny looking sight in our camouflage suits and all painted up among the neat uniforms of the Navy.”

Lt. (jg) Walter O. Pierce, USN (PBY Pilot) – “We had to keep the engines idling and they had to approach us from the side, which was difficult, but Lt. McGowen was very, very efficient, and took care of his men very well. When we came to pick them up, we watched for their signal on shore so we knew where to land, and he did that very well. That’s how we landed to pick him up. The scouts were in good spirits when we picked them up. They said that they could reach out and touch the Japs, that’s how close they were.”

Pfc. Robert W. Teeples (Barnes Team) – “The next night we flew back up and arrived at our rendezvous point just as it was getting light. As we landed we could see a boat coming out from shore. There was a little problem in picking up the team as the pilot had to keep the aircraft moving for a quick takeoff. We finally got the team aboard and, if I remember correctly, they let the air out of the rubber boat and left it.”

Lt. William F. “Bill” Barnes (Team Leader) – “This PBY pilot was so nervous. We were about 200 miles north up at this island [Los Negros] and what we tried to do the first night was sit the seaplane down, but the water was so rough that he was afraid to. So, we flew 200 miles back, and the next night we came back up. We finally got McGowen in there, but he was only going to stay in there for 24 hours, so 24 hours later we came back. I was the contact, in other words, I handled a flashlight and McGowen had a flashlight. He flashed his light and I flashed back to him to let him know that we saw him. As the pilot of the plane was swinging around, a Jap plane flew about 100 feet above us—I don’t know what he was thinking about—but anyway, he swung it around and headed it toward shore, then he swung it back out toward the sea. In the meantime, McGowen’s team had gotten out to the plane. So, the pilot maneuvered the plane again and almost took McGowen’s head off. The propeller knocked his hat off, but he missed him. He came on in, and I got the boat and picked it up and held on to it while they crawled over my back onto the plane, then I ditched the boat out into the water. I don’t know what happened to it, but I guess the Japs got it.”

Patrol Squadron VP-34 (War Diary – 28 Feb 1944) – “Lieut. (jg) Pierce (08491) landed off the south shore of Los Negros Island and embarked the Army Rangers [Alamo Scouts] who had been put ashore on 27 February. Lieut. Merritt (08139) covered the operation.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Feb 1946] – “We were taken immediately to 6th Army Headquarters and they had a huge conference room filled with more brass than I ever saw to get our report. I was a little nervous at talking to such a group of men, but it wasn’t too bad. Each of my men was questioned separately. It was then I learned the importance of our mission, for they told me that a task force (one squadron) of the 1st Cavalry Division was already on its way to make a landing there. I made the remark that it seemed rather foolish to send a task force of about 1000 men to land against about 1000 Japs already emplaced. I don’t think that the brass believed too strongly my estimate of the number of Japs, but the last I heard about the enemy dead of the operation that followed, a thousand dead Japs were counted. Since the task force was under radio silence, I was sent out in a PT boat to intercept them and make my report. Went aboard the flagship and talked with the commanding general of the task force, General William Chase, and he gave me what I’d consider the third degree and asked a bunch of silly, almost stupid questions. For example, when I tried to describe the first two Japs I saw, the conversation ran as follows: ‘I saw two Japs in a house’. ‘What did it look like?’ ‘I don’t know. All I could see were silhouettes.’ ‘How do you know they were Japs?’ ‘I don’t. I thought they were Japs.’ ‘Well, you saw two silhouettes in a house—what kind of house?’ ‘I don’t know. I couldn’t see the house.’ ‘How do you know it was a house?’ ‘Because I saw the window.’ ‘How do you know it was a window?’ ‘I don’t. All I saw was a square with a lighted background and two dark silhouettes framed in it.’ ‘Well, next time don’t tell me what you thought you saw, but what you saw!’ ‘Yes, sir!’ Then there was a strange silence, and I felt like telling him to go to hell or better, or just where I’d been, which was worse. I did get a bit of satisfaction when I was describing the Jap that walked by the trail close to me. I told him I thought it was a Jap, since he looked like pictures of Japs I’d seen. He asked, ‘How far away was he?’ I said, ‘Ten feet.’ He looked over at a table and said, ‘About that far?’ I said, ‘No, sir, closer than that.’ He said, ‘But of course you were lying down in the brush.’ I said, ‘No, sir, I was standing up and there was nothing more between him and me than between you and me.’ Then I laughed at him and asked, ‘Can you understand that?’ He replied, ‘I think so.’ I said, ‘I want you to know so, or I’m just wasting my time?’ He got mad, but the interview went pretty well from there on. I think it was easier to make the patrol than it was to make the report to such an exacting fellow.”

USS Reid (War Diary – Feb 1944) – “[27 Feb] Moored as before. Underway at 1730 and anchored off Cape Sudest at 1850. 1900 War Correspondents R. Shaplen, Newsweek, and O.W. Clements, Associated Press, reported aboard. 2220 Rear Admiral W.M. Fechteler, U.S. Navy, and Staff came aboard with Brig. General Chase, Commander, Landing Force. [28 Feb] USS REID is formation guide and destroyers have formed screen ahead and on the bow…Task Group is en route to the Admiralty Islands…When joined at 1400 by USS FLUSSER, USS SMITH, USS MAHAN, USS DRAYTON, USS WELLES, USS BUSH, the Task Group formed in the cruising disposition prescribed by the Op-Plan. At 1415 Task Group 74.2, composed of USS PHOENIX, USS NAHSVILLE, USS HUTCHINS, USS BEALE, USS DALY, USS BACHE, passed abeam to starboard heading north. While the USS REID stood into Dregor Harbor, Commander Task Unit 76.1.3 in USS FLUSSER assumed Tactical Command. MTB [Motor Torpedo Boat] brought officers alongside, and after a conference with the Admiral and staff, the officers left the ship in MTB. [29 Feb] 0614 Went to General Quarters. Upon arrival at Los Negros Island, the APD’s proceeded to transport and destroyers proceeded to their assigned fire support area. At 0740 bombardment of the beach was initiated by the USS PHOENIX and USS NASHVILLE, the destroyers commenced bombarding shortly thereafter…0826 First wave of landing craft was taken under fire by shore machine guns which were attacked by destroyers standing in close to the beach to support the landing.”

Rear Adm. William M. Fechteler, USN (Cdr – Task Group 74.2) – “On the evening of D-2 day information was received that put an entirely different aspect of the whole operation. Army scouts who had gone ashore that day, or the day previous, on Los Negros Island from the Catalina, reported that the area southwest of the Momote airstrip was ‘lousy with Japs.’ This laid the previous intelligence information from air reconnaissance open to suspicion. The need for all available gunfire support was apparent. Subsequent developments proved that the scouts were more nearly correct. Within a week after the initial landing First Cavalry Division had buried a Jap for each cavalryman landed on D-Day, with estimated total garrison of between 4000 and 5000 troops. Accordingly, Commander Task Group 74.2 was requested to have his cruisers bombard the area examined by the Army scouts, and to have his destroyers take over the area assigned destroyers in Fire Support Area No. 3. This permitted doubling the number of destroyers in Fire Support Area No. 2…”

Toyamo (Japanese soldier on Los Negros) [War Diary – 29 Feb 1944] – “Received bombardment from enemy ships.”

Lt. Col. Frederick W. Bradshaw (Director of Training) [Letter to Lt. Col. Fred Stoff – 4 Mar 1944] – “Dear Fred: The 2nd Bn, 158th has done it again! Your boys, and mine; 2nd Lt. John R.C. McGowen; Pvt. Raul V. Gomez; Cpl. Walter McDonald; Cpl. J.A. Roberts; S/Sgt. Caesar G. Ramirez; and Pfc. John P. Leugoud, have accomplished, to my way of thinking, the most dangerous and profitable reconnaissance mission yet to be undertaken in the SWPA. On the morning of 27 February, at 0715, they landed by flying boat off the south coast of Los Negros Island, in the Admiralty Group. They rowed 500 yards in a rubber boat in broad daylight to the hostile shore. They remained in the area all of that day and night and were taken off the next morning by flying boat. They traversed a considerable portion of the enemy territory and were in dangerous quarters at several times; one time being within ten feet of a Jap patrol which passed them by. There are many details about their mission I would like to tell you, but they will have to be kept until you see them sometime.

Needless to say, I am as proud of them as I can possibly be and I know that you join with me in that pride. They are a great bunch of boys and damn good scouts. They think the world and all of you and are always singing your praises. I am just a little jealous because I feel that all during their mission there was a little feeling in the depths of their hearts that they were doing the job for you and for me; so I guess we will just have to share the honor they have done us. Practically all of the boys you sent me have done a grand job. I know that you would liked to have had them with you on your job and I can say for them that they would liked to have been with you; but good soldiers as they all are, they have stuck by the guns where the powers that be say they can best serve. I am sure that General Krueger will let me release them to you at some future date…”

Lt. Col. Gibson Niles (3rd Director of Training) – “While the team had been unable to carry out its mission completely, in that it had been unable to reach Momote Airstrip because of unexpected enemy activity in the area where the trenches were observed, that intelligence in itself confirmed the belief that the enemy occupied Los Negros in considerable strength. Defensive positions southwest of Momote Airfield were located, and the general physical condition of the defenders determined. The intelligence gained by this mission enabled the Air Force to plan more accurately the bombing of Los Negros, and assisted the Task Force commander in his planning of the initial landing. Concerning advanced reconnaissance in Pacific operations of this type, this first Alamo Scout mission proved the soundness and practicality of employing small teams in this manner…Captured documents strongly indicated that the landing had been observed by the enemy.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Letter – 29 Feb 1944] – “Dear Mom & Dad: I’ve really been having the time of my life. I’ve ridden in and on more things than you can imagine, and been places you could not believe, even if I could tell you—that is before today. Actually, I’m happier right now than I’ve ever been before in my life, and even prouder than when I got my master’s degree. Yippee!! See, your son is slightly conceited (even if he is still a 2nd lieutenant). And yet mom, you are still worried about me. Why, if I had my choice of all the jobs in the Army, or world for that matter, I’d take the one I have. It is clear and only lasts for a few days at a time. And (conceited again), it requires all of my ability. This is the first time I felt that I had the chance to be of any use. In fact, in one day I think I earned all the salary I had gotten since I’ve been in the Army. I have a clear conscious now. It’s a good feeling. The best I’ve ever had.”

Unidentified Japanese Army Officer on Los Negros (Letter to Gen. Imamura – 3 Mar 1944) – “On 27th [February] part of enemy landed on the southern beach of Hyane; thereafter, its main force landed at Hyane Harbor. I think the landing on Southern Beach was a so-called ‘Feinting Operation.’ While Baba Battalion in Southern Sector was concentrating its attention to said area, we were ‘Fooled.’”

Maj. Franklin M. Rawolle (Asst. G-2) [Letter to Bradshaw – 9 Mar 1944] – “The citation for McGowen and his team has gone in but how soon it will come is difficult to tell. These boys deserve all the credit in the world for a helluva lot of sheer guts besides doing a bang up job of scouting. I wouldn’t have blamed them had they turned down the deal. We tried to block it but the General was adamant.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Letter – 5 Mar 1944] – “Dear Mom & Dad: What a reception we got back here at camp. It did my heart good and I think I shall have to be getting a new hat a couple of sizes larger. We are quite the heroes, and excuse me if I seem to brag, rightly so. I had to get up and make about an hour speech to the boys about my experiences. Also have to make another tomorrow. They gave us a party the night we got in, and I had an honest to goodness hangover the next day. Boy, never again!”

Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger (CG, 6th Army) [War Diary – 20 Mar 1944] – “Awarded Silver Star medals to one officer and five enlisted men, all members of the Alamo Scouts.”

Lt. John R.C. McGowen (Team Leader) [Letter – 21 Mar 1944] – “Dear Mom & Dad: I really did feel proud at the presentation ceremony. It was a new experience for me. It felt pretty good to have the General pin it on me and shake my hand with all the staff looking on.”